Click here to subscribe today or Login.

In 1936, the Wyoming Valley had no reason to think that Good Friday would be anything but the usual quiet day of prayer and repentance in preparation for Easter.

Instead, three people would be dead by evening and several more would be gravely injured while authorities tried trying to figure out who had sent six bombs through the U.S. Mail.

That act of domestic terrorism happened on April 10, 1936 — 80 years ago today — and has been known ever since as the Good Friday Bombings.

At about 9:30 a.m. that day, a small package marked “sample” arrived at the East Northampton Street, Wilkes-Barre, home of Thomas Maloney, who had been a leader of a dissident mining union group two years earlier.

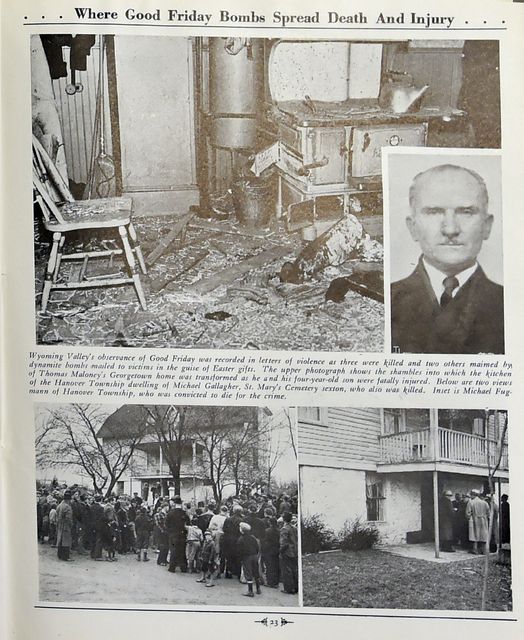

“My father thought it was a gift and he opened it and it was a bomb,” said Maloney’s daughter Margaret in 1986, 50 years after the bombings. The blast tore off Maloney’s hand and injured his young son Thomas and then-teenage Margaret, who’d been with him in the kitchen. His wife Elizabeth, who’d been upstairs, escaped harm.

Neighbors took the injured to a hospital.

Authorities quickly arrived at the Maloney home. Fearing that the explosion might be connected to the hot mining union issue that had roiled the community, they decided to focus on the mail and try to intercept any additional bombs.

They were correct. Five more bombs were in the mail that day, all in innocent-looking cigar boxes disguised as gifts.

One of the intended targets was spared by sheer luck. Former County Sheriff Luther Kniffen of Wilkes-Barre tried to help his secretary open the package, only to damage it and send the broken bomb tumbling harmlessly to the floor.

Another target saved himself by being on the watch as word spread. Harry Gouldstone of Kingston, a mining superintendent, had told his family to keep away from any unexpected packages. They did, and called authorities when a box arrived.

Two more bombs were stopped in the mail. They were intended for county Judge Benjamin Jones and James Gorman, a state Anthracite Conciliation Board umpire.

But there was a sixth bomb.

Late that afternoon a package marked “sample” arrived at the home of Michael Gallagher, a member of the Hanover Township School Board and caretaker of St. Mary’s Cemetery. His son-in-law Clinton Lehman and Lehman’s young sons Donald and Clinton Jr. were visiting while the two men’s wives were at church.

Donald Lehman carried the day’s mail into the kitchen and gave it to Gallagher, who was in the room with the boys’ father.

“When I saw it was a box of cigars it was of no interest to me, and so I walked out of the kitchen,” said Donald many years later. That action might have saved his life.

Gallagher set the box on his lap and opened it. The blast killed him and badly injured son-in-law Clinton.

Within days three of the victims of the two blasts had died: Thomas Maloney and his son, along with Michael Gallagher. Authorities were mystified as to why Gallagher had been targeted since he had nothing to do with mining affairs. They concluded that a confusion of names had caused bomb six to be sent to the wrong person.

Investigators from Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne county and the Pennsylvania State Police, as well as experts from the New York City Bomb Squad, went into action.

It didn’t take long to analyze the surviving bombs and determine the mail boxes into which they had been placed. Cigar manufacturers in Philadelphia identified the local stores to which the boxes had been shipped. A clerk in Schulte’s Store on Wilkes-Barre’s East Market Street was able to identify a man known as Michael Fugmann, already a suspect, who had asked him for the empty boxes.

In trial, Fugmann was revealed as a deserter from the German Army in World War I and a figure in the contentious anthracite region mining union dispute, having had a falling-out with onetime ally Maloney. The prosecution also displayed materials from Fugmann’s Hanover Township home that they said linked him to the bombs, including the specific foreign-made explosives. They even had photos from the war showing Fugmann as a member of a blasting crew in Germany.

He was found guilty. The defense fought the death penalty, but in July of 1938 – more than two years after the bombings – Fugmann was strapped into the electric chair at Rockview State Penitentiary and executed.

Survivors went their separate ways after the bombings. Luther Kniffen, who was saved when one of the bombs malfunctioned, would later become mayor of Wilkes-Barre.

One of the Lehman children, Clinton Jr., became a doctor. Even in 1986, 50 years later, he and his family had not forgotten the bombings.

“Every Good Friday we call Black Friday at our house,” he said.