Click here to subscribe today or Login.

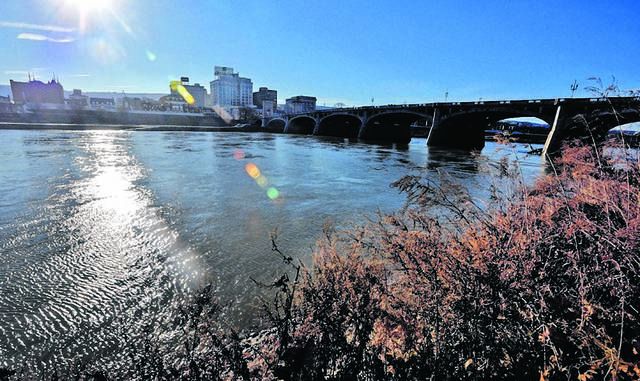

Release of sewage into the Susquehanna River in New York State often comes up in the debate about a regional stormwater fee here.

The gist of the complaint: Why should local property owners pay more to clean up the Susquehanna and Chesapeake Bay when the upstream state is not stopping the sewage?

Except that officials in New York say they are taking steps to address the problem, and there is a state plan reflecting that.

Like Pennsylvania, New York must meet specific targets reducing phosphorus, nitrogen and sediment into the river mandated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

All seven states in the bay watershed must develop three-phased “Watershed Implementation Plans,” or WIPs, outlining how they plan to comply in the wastewater, stormwater, agriculture and other sectors over the next five years.

Reconstruction of the Binghamton-Johnson City Sewage Treatment Facility is a key part of meeting the state’s wastewater targets because it is the largest wastewater treatment facility in the New York portion of the bay watershed, New York’s WIP says.

Significant flooding in 2011 inundated the treatment plant, causing major structural damage to its biological aerated filter treatment system that made the facility inoperable, the WIP says.

“Failure at the plant has prevented New York from being able to meet interim nitrogen reduction targets in the wastewater sector, though it is expected that New York will meet its wastewater sector targets when the plant is fully operational,” the WIP says.

With ongoing construction, the facility now has partial treatment capabilities but is still not performing at a comparable pre-flood level.

NYS order

To force restoration of treatment capabilities, the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation negotiated a consent order with Binghamton, the village of Johnson City and their Joint Sewage Board setting an Aug. 31 deadline this year to both substantially complete reconstruction and meet sewage discharge limits.

The plant construction must be fully complete by June 30, 2020 under the order, it said.

Binghamton Deputy Mayor Jared Kraham said the new plant will “better handle the flows,” improve treatment and help the state meet its reduction mandate.

After taking office in 2014, Binghamton Mayor Richard C. David determined a new state-of-the-art plant was warranted to fully address treatment demands, Kraham said. In addition to the flood damage, a concrete wall at the facility had collapsed before the flood.

“This is an important piece of infrastructure for the environment and not one that people historically wanted to tackle,” Kraham said.

The new plant is expected to cost between $270 million and $275 million, Kraham said.

Wastewater customers in the 12 municipalities serviced by the plant will have to pay the portion of the project not covered by flood-related federal reimbursement, awards from pending litigation against firms involved in the design and construction of the collapsed wall and several state grants, he said.

“When the project is complete, the plant will meet those environmental standards for the first time in recent history,” he said. “The can had been kicked down the road for decades.”

More than 841.3 million gallons of sewage mixed with stormwater has been dumped into the Susquehanna since Sept. 6, 2018 from the greater Binghamton area, state reports show.

While sewage is included in this mix, Kraham said most of the volume is stormwater from combined storm/sewer outfalls that must send untreated water into waterways to prevent flooding and back-ups in properties during heavy rain.

As in the Wyoming Valley and other parts of Pennsylvania, New York officials are attempting to tackle costly separation of combined systems when funds are available, Kraham said. Rain gardens, water-soaking riparian buffers and new development practices reducing impervious area also are part of New York’s plan to reduce the quantity of stormwater sent to waterways, according to Kraham and the WIP.

“They’re unique challenges, but we each play a part in the ecosystem and Chesapeake Bay Watershed,” Kraham said.

Approximately 642,000 residents live in the 6,250-square-mile New York Chemung and Susquehanna rivers watersheds draining into the bay, according the WIP.

Treatment needed

Wastewater treatment plants process water from homes and businesses, which contains nitrogen and phosphorus from human waste, food and certain soaps and detergents, according to the EPA.

Some wastewater treatment plants are able to remove more nitrogen and phosphorus from their discharges than others depending on their equipment and how they treat wastewater, the agency said.

In Pennsylvania, wastewater treatment plants had to meet limits on nitrogen and phosphorus that can be sent to the river — known as “cap loads” — about a decade ago, said Jim Tomaine, executive director of the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority, which agreed to handle a local regional stormwater pollution reduction program on behalf of 32 municipalities that is being funded by the new stormwater fee.

The authority also provides wastewater treatment in 36 municipalities.

Tomaine estimated about $4 million was spent on plant improvements and other work to meet the wastewater mandate, which is far less than new facility construction required in some areas.

The authority ended up surpassing its reduction requirements, to the degree it can sell credits to other entities that are not in compliance, said authority Solicitor William Finnegan.

Last year, the authority generated more than $550,000 selling such credits to other wastewater facilities and private industries, said authority Operations Director Bernard Biga. He estimated credit sales generated approximately $2.5 million over the last decade.

Authority officials are willing to start giving those nutrient credits to the regional stormwater group instead of selling them to outside entities, which would reduce the pollution reduction projects that must be funded by the stormwater fee, Tomaine said. However, the state has no such credit transfer option in place for the stormwater mandate at this time, although it may be possible eventually, he said.

The authority removes about 2 million pounds of nitrogen from wastewater annually and puts out less than half of the 584,000 annual cap load for nitrogen, Biga said.

One of the authority’s primary techniques involves turning blowers on and off to adjust oxygen levels supplied to microorganisms to coax them to gobble up certain molecules.

“We spent a lot of years coming up with a completely new way to treat wastewater,” Biga said.