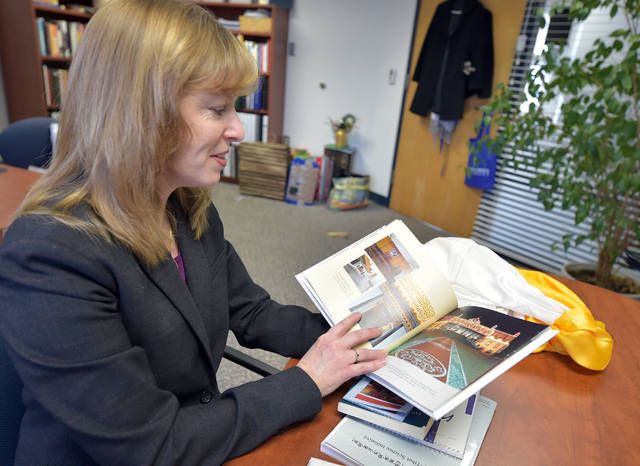

Heidi Manning, the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Misericordia University, discusses her time teaching monks in Tibet about science.

Aimee Dilger | Times Leader

Click here to subscribe today or Login.

DALLAS TWP. — Heidi Manning could handle the frequent stops as her lessons were translated to Tibetan. She demonstrated mastery of the Tibetan singing bowl with aplomb. But when a monk with scant science education asked the Misericordia University physics professor to “define color,” that was a bit of a poser.

“Many were sent to the monastery when they were just 5 or 6,” she explained of the Tibetans being raised in India ever since the 1959 Chinese occupation of their homeland sent the Dalai Lama and some 100,000 Tibetans into exile. “For many, the only way to assure food, clothing and an education for their children was to give them up to the monks.”

That led to a generation of Tibetans with a rich training in religion and philosophy but very little modern science. Seeking to change that, the Dalai Lama established a six-year partnership with Emory University known as the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative that brought more than 200 educators from this country to three Tibetan communities in India. In 2017, Manning was one of those teachers. This year, she went back to see that group of 233 students graduate the program.

In an office adorned with an Astronaut Barbie (Mint-In-Box) to that singing bowl, Manning gladly pulls out the Khata, a long scarf presented to her and other visiting teachers as a symbol “of honor and recognition.” She has a book by and from the Dalai Lama, “The Universe in a Single Atom.” And she has the memory of being within about 6 feet of His Holiness at the graduation, an experience she concedes was not quite enough to convert her to Buddhism but did add to her admiration of the man.

“He is very open, very progressive,” she recalled. “He does not see a conflict between modern science and Buddhism.

Thus the ETSI program and her two trips to India — 16 hours non-stop from Newark, N.J., to Mumbai, and another day to the monastery. The six-year curriculum for monks began in 2014, so she taught them in their fourth year, which was also the first year the program was extended to Tibetan nuns (there are no co-ed classes), which led to an unexpected discovery: Both men and women shave their heads in the monastery, and wear the same robes.

Manning recalled teaching a class and wondering where the nuns were, discovering some took a class nearby when a colleague pointed them out.

Most of her students ranged from their 20s into their 40s, but the shaved heads made it difficult to judge age, she said. They were very bright, dedicated and intelligent, but the lack of science education coupled with the inquisitive nature of their religious and philosophical training led to some curious situations.

“They did not know fractions,” she said. “If I say ‘one-quarter and one-half equals what’ here, people know it’s three-quarters. I had to figure out how to teach math.”

Similarly, many of the monks and nuns had no idea what atoms are. When taught the concept, one asked, “What would the world be like without atoms?”

(Short answer is that nothing would exist as we know it without atoms and the forces that draw them together into molecules).

Another student “asked me to define color,” she said. She opted for an answer anchored in physics and human experience. “It’s packets of energy we can see as colors,” she explained, noting the monks and nuns had no knowledge of photons, light waves and the visible and invisible spectrum seen by the human eye. Her explanation evoked an outbreak of applause.

Considering Manning’s work experience includes three stints with NASA and specialization in planetary atmospheres, this may not have been the most academically challenging thing she’s done. But from the way she talks, it was one of the most rewarding.

“I would love to go back.”

Reach Mark Guydish at 570-991-6112 or on Twitter @TLMarkGuydish