Tom Brady set the NFL record for completions in a season, but his overall level of play fell off as the Buccaneers lost in the first round of the playoffs.

Chris O’Meara | AP photo

Click here to subscribe today or Login.

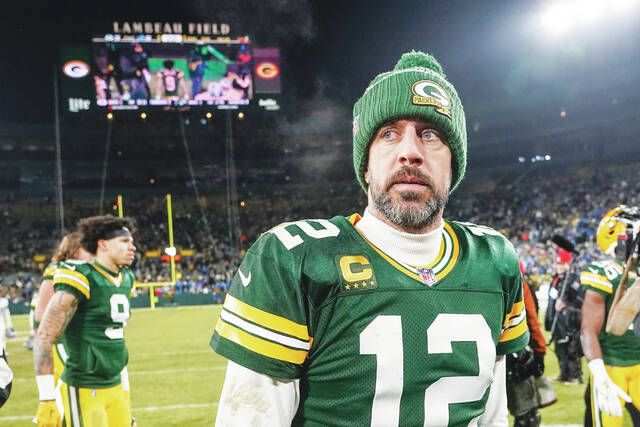

When 12-year-old Michael Jackson and his brothers sang their hit song, “Never Can Say Goodbye” in 1971, they certainly weren’t singing about Tom Brady’s 40-day retirement last year before coming back to quarterback the Tampa Bay Buccaneers this season. And they weren’t referring to the annual “will he or won’t he play next year” dance Aaron Rodgers has with the Green Bay Packers.

The Jackson Five were singing a love song, but there’s not much to love when athletes play past their prime or hang on to win one more championship or break one more record when there isn’t too much left in the tank.

To be fair, Brady and Rodgers both had good statistics this year. Brady completed an NFL record 490 passes for 4,694 yards, 25 touchdowns and nine interceptions. Rodgers completed 350 of 542 passing attempts for 3,695 yards, 26 touchdowns and 12 interceptions.

Several teams would love to have this level of production from their quarterbacks, and they will probably get in line for a chance to have either of these future NFL Hall of Famers suit up for them.

And that, you see, is the problem. Neither led their team to a winning season. The Bucs and the Packers were both below .500 and the only reason Tampa made the playoffs is that its division was so weak. They may have put up some impressive numbers, but it was not in the same style as before.

There are some things true sports fans don’t want to see, even if it works out better for their favorite teams. The Bucs were defeated well before halftime in their wild card game and many of Brady’s passes floated like ducks. And when the Packers had to beat the Detroit Lions to have an opportunity to make the playoffs, Rodgers turned in a dismal 38.7 quarterback rating.

That isn’t the way to remember football legends such as these.

When players have earned elite status in their sport as both Brady and Rodgers have, it’s better to remember them hoisting Super Bowl and MVP awards than to see them leaving the field defeated.

Emmitt Smith was an all-time great running back for the Dallas Cowboys, winning three Super Bowls and earning eight Pro Bowl designations. When the Cowboys felt it was time to move on, Smith played two seasons with the Arizona Cardinals. He gained 1,193 yards over that time with Arizona, a level he surpassed in a single season nine times with Dallas.

I’m a Philadelphia Eagles fan, so you know what I think of the Cowboys. Even so, it just wasn’t right to see Emmitt Smith wearing the bright red Arizona uniform on his way to the career rushing record of 18,355 yards.

That was a tremendous achievement, but he was no longer putting fear into defenses when he finally crossed the finish line, and he should have been a career-long Cowboy.

The “Never Can Say Goodbye” syndrome is not limited to football. It’s alive and well in other sports, too.

I went to my first Major League Baseball game in 1966 in Philadelphia to see the Phillies play the San Francisco Giants and Willie Mays. He homered that night and played with his usual flair and greatness. But when I visited Shea Stadium in New York for a 1973 game between the Mets and Los Angeles Dodgers, it was clear that Mays, then 43, was running on fumes and had played too long.

One of the great things during my years as a Phillies season ticket holder in the late 1970s and early 1980s was the pleasure of watching Steve Carlton pitch.

A four-time Cy Young Award winner, 10-time All-Star and two-time World Series champion, the man known simply as “Lefty” won 329 games and lost 244 with a 3.22 earned run average and 4,136 strikeouts over 24 seasons. He won 20 or more games six times during his career and his last relatively good year was 1984 when he went 13-7 with a 3.58 ERA.

You knew when Lefty was pitching the Phillies were likely to win, and the game would be played quickly. Carlton didn’t waste any time on the mound and usually beat his opponents in two hours or less. He had no need for a pitch clock, unlike most pitchers today.

Carton left the Phillies in 1986 and played for the Giants, Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians and Minnesota Twins over the next two seasons, winning just 11 games while losing 21 before finally calling it a career. That isn’t the way you want to see a Hall of Fame great go out.

Boxing fans knew Muhammad Ali as one of the best fighters ever, and he was often ranked as the greatest heavyweight of all time. He won a gold medal at age 18 in the 1960 Summer Olympics and the heavyweight championship at age 22 when he defeated Sonny Liston. His three fights with Joe Frazier beginning in 1971 were epic, and then Ken Norton broke Ali’s jaw while handing him the second loss of his career in 1973.

Ali regained the heavyweight championship at age 32 in 1974 when he defeated George Foreman. He employed the “rope-a-dope” strategy and allowed Foreman to punch himself out before knocking an exhausted Foreman out in the eighth round.

Beginning in 1976, though, he clearly was not the fighter he used to be, winning a controversial decision over Norton and announcing his retirement afterward.

This first retirement didn’t last long, and in 1977 he took several hard shots to the head while defeating Earnie Shavers. His longtime doctor Ferdie Pacheco urged him to retire, but Ali ignored the advice and lost the championship title to an inexperienced Leon Spinks in 1978. He won a rematch later that year to become the first fighter to become heavyweight champion three times.

Ali retired a second time but again it didn’t last long, despite his beginning to experience vocal stutters and hand tremors. Incredibly, he was medically cleared to fight, and he returned to the ring in October 1980 against champion Larry Holmes. The Easton Assassin beat Ali easily, the only time Ali lost by the fight being stopped before going the distance.

While many people point to the Holmes fight as a contributor to Ali’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and pleaded with him to retire permanently, he didn’t comply until losing a December 1981 fight to Trevor Berbick. It was a sad way for the champion often called “The Greatest” to leave the ring.

With so much money involved today, it’s even more difficult for athletes to end their playing careers. I appreciate Hall of Fame third baseman Mike Schmidt, who abruptly retired in May of 1986 while the Phillies were on a West Coast trip.

With tears running down his face, Schmidt told the media his reason for walking away was simple. He was used to being the best and knew in his heart that he no longer was.

That’s a good measuring stick for other great athletes to follow. It’s too bad they rarely do.

David Jolley is a baseball fan and historian, public relations and marketing communications consultant, writer, and the author of ‘A Good Cup of Coffee … Short-Time Major Leaguers and Their Claims to Fame.’